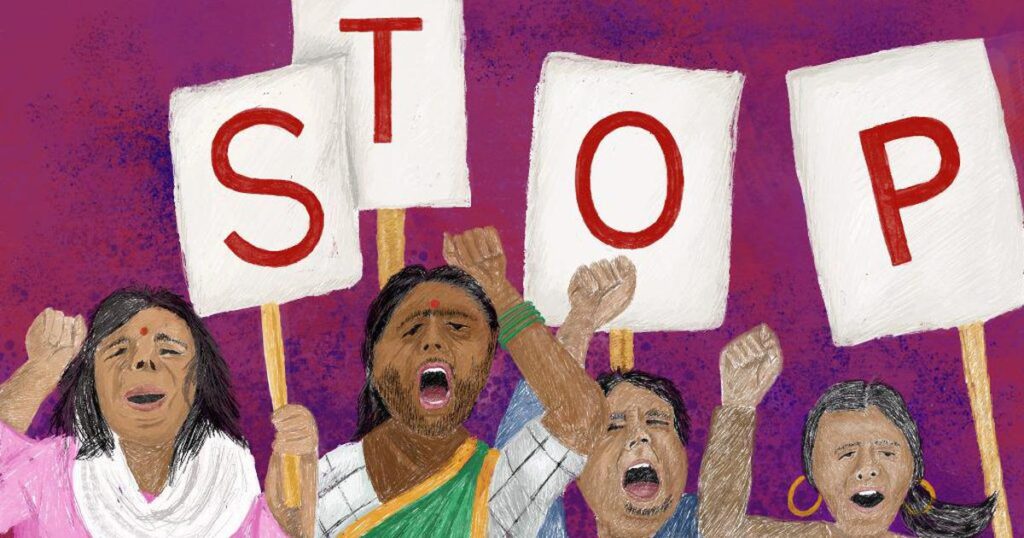

The kind of news (and their intensity) on incidents of gender-based violence coming in every day serve as a reminder of the urgency to have this conversation.

The gendered cost of violence

By Vanita Ganesh, Digital Media Coordinator, Shadhika

November 10, 2022

Reading Time: 6 minutesTrigger warnings: Instances of types of violence, mentions of sexual abuse and rape.

In my short time as a communications professional, working on a program for 16 Days of Activism is often a bittersweet experience. It is a reminder of how far we’ve come and, simultaneously, of how far we have left to go.

In 2021, Seven in 10 women said they think that verbal or physical abuse by a partner has become more common. In that same time period, six in 10 felt that sexual harassment in public spaces has worsened*.

This is the reality that women, girls, and other gender minorities in India experience. India is one of the biggest democracies in the world yet women and girls have few recourses to protect themselves. According to government data released in this past September, 2021 recorded the highest number of crimes against women ever. And this is based on cases reported to the authorities. Evidence points to an estimated 99.1% of sexual violence cases falling through the cracks.

What about the violence and aggression that go undocumented? How do we begin to talk about solutions when so much violence can also manifest itself through financial, mental, or emotional abuse or control? Suppose our so-called solutions do not acknowledge that violence is also intersectional and that it can seep into every aspect of a person’s life. How can we talk about ending gender-based violence (GBV) in these conditions?

Rani (name changed) a distant aunt of mine was everything a modern Indian woman is expected to be. She works in a tech company, is a sensible and down-to-earth person, and married someone her parents chose for her. I did not know that her husband put her under mental duress for the smallest reasons.

Came home late? Spent too much time at her parent’s home? Got a promotion at work? All of these were causes for mental abuse and restrictions over her own finances. Many relatives knew of this behavior and dismissed it as just an ‘overbearing’ husband. They ignored the fact that she, like many women and girls in abusive households, could not get out of the situation.

The volume and the intensity of news covering incidents of gender-based violence every day serve as a reminder of the urgency to have this conversation. It also confirms that individuals belonging to underserved and minority communities face a significantly higher incidence of physical, emotional and other kinds of violence directly linked to their gender, sexuality, caste, ethnic, religious, or socioeconomic identities. According to the National Family Health Survey 2015-2016 (NFHS), sexual violence rates were highest among women from Scheduled Tribes (Adivasi or Indigenous Indians) at 7.8%, followed by Scheduled Castes (Dalits) at 7.3%

On social media and the internet, we discuss these incidents and call for accountability. But we often quickly move on to the next topic trending in the news cycle.

Yet gender justice work needs consistency. We need to ask ourselves uncomfortable questions that often do not have answers, just directions to possibilities. It requires collective work, trust, allyship, and a strong connection with the field while acknowledging that the ‘field’ is not a vague concept devoid of socio-cultural realities. This work needs us to carefully consider the field data and the impact on the ground and remember the people behind the impact–people with complex realities. A cookie-cutter solution will not bring the outcomes we so desperately wish for.

At Shadhika, when we follow Shadhika Scholars’ and local partners’ leadership, we can see evidence that a hyperlocalized approach that adopts an intersectional lens can inspire real systemic change within their communities and their families.

For instance, the National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5) tells us that 48% of girls in India with no education were married below 18 years of age, as compared to only 4% among those who attained higher education. Education holds protective powers and Shadhika is pushing on key levers to meaningfully reduce gender-based violence.

For instance, in 2020, here are the outcomes of Shadhika’s work:

- 90% of girls who participated in Shadhika-funded activities completed secondary school

- 100% of Shadhika Scholars graduated from college

- 87% of Scholars’ parents changed their attitudes about women attending college

- 60% of women part of Shadhika’s Initiative to End Gender-Based Violence (GBV) funded by DAWN reported physical violence stopped in their homes.

Yet no two Shadhika partners approach girls’ and women’s rights and GBV prevention the same way.

Instead, the results above are proof that what will make a difference is consistent, grinding, and foundational work that is tailored to each local context and makes choices available for women and girls. Choices that will empower women and girls to leave situations of abuse and violence, to choose a life on their own terms.

With constant exposure to dismal and triggering news about the state of the world, it is quite easy to get lost in despair. Yet, the courage and determination displayed by Scholars and program participants, supported by the partner sites, light our way forward. To quote Shadhika’s Executive Director My Lo Cook, “Let us choose to practice hope, and by putting one foot in front of the other, let us do what we can with what we have, exactly where we are.”

*UN Women (2021), Measuring the shadow pandemic: Violence against women during COVID-19.

If you or anyone you know are facing domestic or intimate partner violence call 1091 (24-hour women’s helpline) for help. Other Domestic violence helpline numbers can be found at India Helpline, Naree, and standupagainstviolence.org.