Blog

"There was a pause. Each girl knew the shared unpleasantness and fear that cripples their agency, mobility, decision-making ability, safety, and freedom."

The pause explains the deep-rooted inequality

By Upasana Saha, Program Officer

December 10, 2019

Reading Time: 5 minutesAs a woman in India, I often hear how lucky I am to enjoy the utmost liberty and independence – especially when I am challenging my society’s accepted gender norms. This seemingly benign remark hides a powerful system of gender inequality. Women in India and around the world can attest to the patriarchy’s power to determine what our lives as women “can” and “should” be. Comments like this are used to undermine women’s aspirations and motivations to shift the status quo.

On a recent visit to Nagepur village, 50 km away from Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh, India, I met a group of adolescent girls and young married women. The village has a large Banarasee saree weaving community. Most families, including their children, are trained and have been engaged in this unorganized and poorly paid industry for generations.

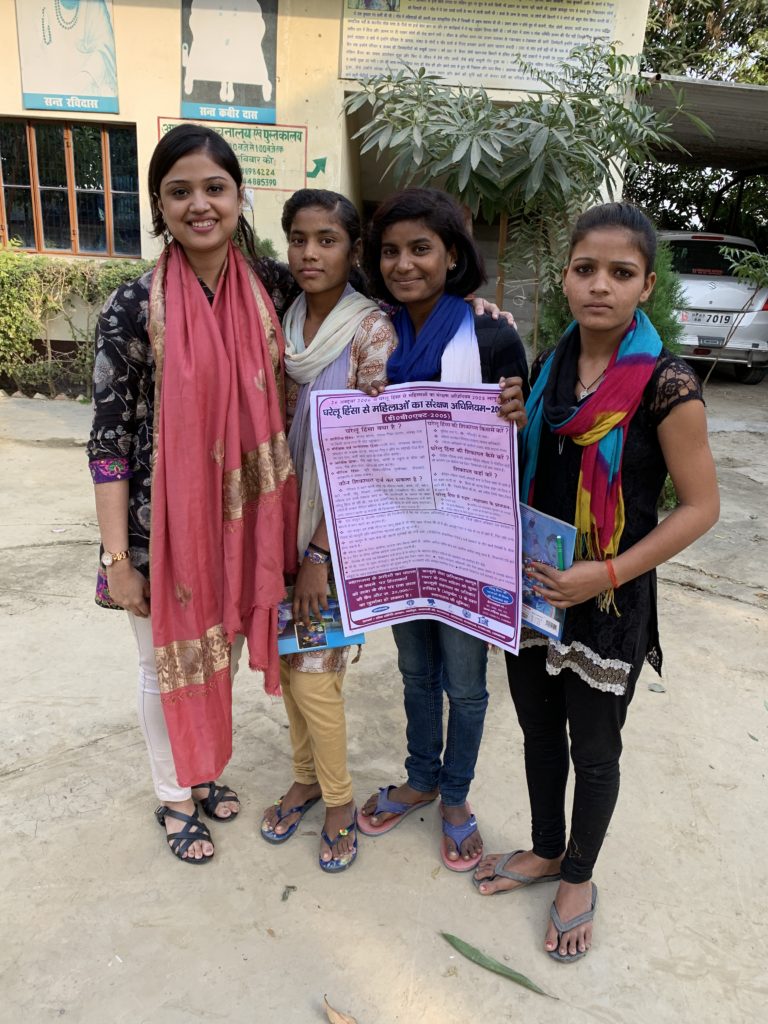

As I started talking to this group of young women, my experiences about women’s freedom didn’t feel so distant. A few minutes into our conversation, the girls circled around me to share their stories and underlying interest to be part of Shadhika’s DAWN Initiative Against Gender-Based Violence, which we recently launched in their villages. The Initiative, underwritten in part by Direct Action for Women Now (DAWN), is a unique program curated by Shadhika and four implementing partner organizations: Asian Bridge India, Grameen Punarnirman Sansthan, Lok Samiti, and Gramya Sansthan in three villages of Varanasi district, Uttar Pradesh. The objective of the program is to engage in multiple layers with men and boys, women and girls, and other “gatekeepers” (police, elected officials, health care workers, media, and others) to systemically address gender-based violence.

I asked the girls about their opinions on violence against women and if it prevails in their communities. There was a pause. Each girl took time to process and articulate her thoughts. Each girl knew the shared unpleasantness and fear that cripples their agency, mobility, decision-making ability, safety, and freedom.

Their emotions and responses weren’t surprising. Throughout the conversation, issues of domestic violence and street sexual harassment were consistently brought up–which relieved a few, made a few angry for being sidelined, and left others feeling the fear of being blamed.

Hearing their experiences reminded me of the status quo of National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), where Uttar Pradesh, a Northern state in India is known for extreme marginalization and discrimination and carries the highest number of reported cases on violence against women–56,011 cases to be exact. I emphasize the word “reported,” as that mechanism in India is poorly accountable due to many factors including low female literacy, the burden of protecting family honor, not to mention a flawed and poor redressal system that paralyses the entire justice process and reinforces victim blaming and inequality.

Though India is among the highest ranked nations for gender-based violence, the issue is truly a global concern. According to the World Health Organization:

1. Violence against women – particularly intimate partner violence and sexual violence – is a global public health problem and a violation of women’s human rights.

2. Global estimates indicate that about 1 in 3 (35%) of women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime.

3. One-third of women who have been in a relationship report that they have experienced some form of physical and/or sexual violence by their intimate partner in their lifetime.

Global reports indicate violence against women is an endemic phenomenon that cuts across the globe irrespective of age, sex, education, demographic, or socio-economic landscapes.

In the past there have been many successful programs and movements focused on addressing violence against women and gender-based violence, yet these programs faced two common challenges: backlash and resistance from men and boys and capped sustainability after program withdrawal.

Being conscious of these two challenges, Shadhika’s effort is to prioritize a collaborative, rights-based and bottom-up approach. By supporting local NGO partners to focus on individual behavioral change as well as institutions and policies, we can begin to shift the systems that perpetuate gender inequality and violent power asymmetries between men and women.

Read more